Poet and playwright Loueva Smith was a Public Poetry reader in 2011. Update: In 2015, she w on the Robert Phillips Chapbook Prize, awarded by Texas Review Press. Her winning collection “Consequences of a Moonless Night” was published in 2016. She is also the author of “The Book of Wool and Fur” a hand-made fur-covered collection of love poems created for the 2010 Houston Fringe Festival. A native Texan, her poems have been published in such journals as DoubleTake and the Louisiana Review, and anthologized in “Goodbye, Mexico,” “Untamable City,” “The Weight Of Addition,” “TimeSlice” and “Vanishing Points.”

on the Robert Phillips Chapbook Prize, awarded by Texas Review Press. Her winning collection “Consequences of a Moonless Night” was published in 2016. She is also the author of “The Book of Wool and Fur” a hand-made fur-covered collection of love poems created for the 2010 Houston Fringe Festival. A native Texan, her poems have been published in such journals as DoubleTake and the Louisiana Review, and anthologized in “Goodbye, Mexico,” “Untamable City,” “The Weight Of Addition,” “TimeSlice” and “Vanishing Points.”

What poet first got you interested in poetry?

Emily Dickinson—she’s the witch who did it to me. That was when I was a teenager, which is when I started writing, although I didn’t start reading my work aloud till much later. One thing is constant with my writing—I’m obsessed. When I lie down to go to sleep at night, I picture myself there at my desk, writing. It deeply validates me—that some part of me is able to speak.

Do you have a ritual or routine that you go through when you write?

I bought a shed and put it in my backyard, added carpet and a desk. I get a really good feeling about going there to write, and entering that space is a very intense part of the writing process. I didn’t always have a room of my own—it’s a sanctuary. I write there a few hours every day, whenever possible. Always with pencils, too—that’s another part of it.

Is that so you can easily erase things?

Not so much that—it’s a very tactile thing. Your hands get all smudged up, and you can feel the work on you. And I have so many notebooks. There’s a notebook for every different type of idea or feeling, spiral-bound, leather-bound—I have one with incredibly fragile paper that I only use for secrets. It’s when I’m trying to sneak up on something elusive.

Are any of the poems in “Consequences of a Moonless Night” from that notebook?

No, I don’t think so. Most of those ideas turned into poems that were in “Vanishing Points,” an anthology I did with Sarah Cortez, Larry Thomas and Jack Bedell about roadside memorials in Texas. There was fear associated with saying what I wanted to say about it, because the people who those memorials were to are dead. I felt that I was interacting with their spirits, and that their spirits knew what I was doing. I wanted to be very respectful about that. Writing has that kind of energy—it comes from the subconscious.

Here is a question from a “Public Poetry” follower: poetry books are often in the non-fiction section of the library. Do you think the non-fiction label is accurate for your poems?

Creative non-fiction is a more accurate description of what poetry is. You’re attempting to own “something” through language. And it feels like that fiction makes it more true—like a Picasso painting. You see the truth through the essence of the piece.

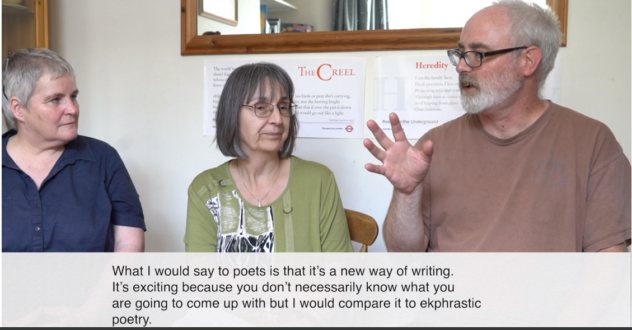

You’ve worked with Lydia Hance, a dancer, who has “danced” your poems. Has seeing your work embodied in dance changed the way to write, and the way you perceive your own poetry and writing process?

That program also involved a painter, Cookie Wells. She painted nude watercolors and incorporated my lines into the paintings. I read the poems while Lydia danced at the gallery where the paintings were displayed. That was an experience that was so humbling, in a way, and so enthralling. It had an energy that seemed to come from a very ancient place in how humans do their storytelling. It was like we had almost accidentally tapped into it. I wish that artists would collaborate like that more.

It sounds beautiful, but probably very time-consuming. Have you ever incorporated dance or movement into your own everyday writing practice?

Yes. Lydia taught me about moving the poem myself, too. So, for poets, if there is something with a line that is bothering you, try walking around in your room saying that line over and over. What kind of gesture would that line be? Start making that gesture, and keep making it bigger. In that way, your body will teach you what you really mean.

How is “Consequences of a Moonless Night” different from your previous books of poetry?

I got it published! Sarah Cortez encouraged me to submit it to the contest at Texas Review Press, and while I was working on it, she pointed out that I had a poem with a moonless night, and later on a full moon night. So, those ended up being the first and last poems in the collection. It has a more cohesive arc than my other books.

Why is access to poetry so important? Why does the world need poetry now?

Did you see the election? Do you know what we need right now, honey? We need poets. We need poets called to action.

Why should poets, specifically, be called to action?

Bcause we are, I believe, deeply sensitive. We are barometers, like roaches are. We have our little antennas up. We know when the light’s gonna come on—we are picking up on the currents of what is happening in our society right now. We would like to heal and awaken people. That’s part of the power poets have always had.