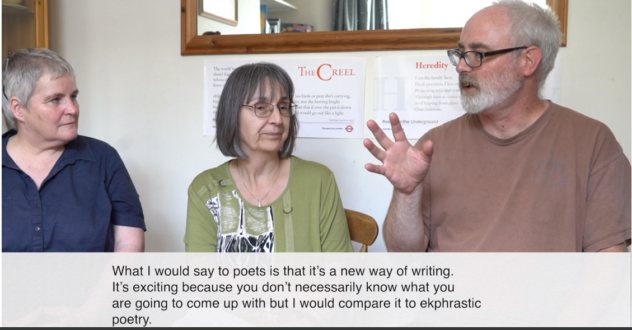

The new summer series line-up features Randall Watson on Saturday, July 11. Travel along on his journeys with poetry you can preview here….

The new summer series line-up features Randall Watson on Saturday, July 11. Travel along on his journeys with poetry you can preview here….

Trailways, August 28, 1963

(for Syble)

We crossed the exhilarating, high-pitched.

Passed the stench and glittering,

the amusement bright, the gradual,

box apartments by the tracks and stations

squatting like bored and patient orphans

waiting for a Sunday market to begin.

Then the green-bordered interstates.

Hay-bales scattered like formalist sculptures, cornfields

with their stiff stalks and rag-doll tassels

limp as puppets hung

in a storage closet.

Side woods snarled with briar and ivy.

Oaks and maples.

Then rummy and old maid

at the little table rearward and nearby

the cramped bathrooms

that stank of chemicals and soap and piss

splattered on the metal floor, flecks

of snow white shaving foam

clinging to the shadowy mirror.

Racks of bags and suitcases and light jackets

dreaming above our heads

like hibernating mammals.

The chrome bright

burnings of the little towns,

those signs for Burma Shave and Stuckeys and

The World’s Largest Rabbit

and men in large hats and fringed buckskin

wearing side-arms on the porch

of a mock saloon.

Birds scrolling the staves of the infrastructure.

Men outside a church

brushing ashes from their sleeves.

Wives and daughters and mothers touching their hair

as if to measure themselves,

waving little paper fans

stapled to paint-sticks

where Jesus kneels, alone

in the midst of his drowsy, sleeping disciples,

knowing the story his body will tell.

And then my grandfather

sitting on the back stoop with his .22

shooting sparrows, which dirty the sidewalk.

Dust blowing off the fields.

Small purple flowers

speckled with dew and foraging ants.

He’s dipping bread in a cup of milk, disregarding

the plate of tomatoes, red as transitions.

Crushing his Pall Mall in the drive.

Pulling two hot 7Ups from the trunk

of his Oldsmobile.

And those boys

in jeans-jackets who gather

outside Peguy’s,

the only women’s clothing store in town,

car hoods raised, adjusting

the air intake or idle, gunning

the engine.

Wiping the oil-stick clean

with a slash of newsprint.

Attuned to the mechanical contrivance.

Discovering their blurred faces in the polished armature.

There near the geographical

heart of the country.

38 North by 97 West.

Entranced by the sheen.

Xalapa

For a month, now, I have been walking the city.

I like the way the girls rest their hands on their boyfriends’ shoulders

to adjust a shoe.

The way a man bends over, back to the wind, to light a cigar.

How the gypsy women roam the park in their long dresses seeking donations.

Their faded brochures. The boys in fandango outside the cathedral.

And the smell of grease and oil at the little garage

is familiar and comforting. The chime of a ratchet or wrench

dropped in a toolbox. The graceful and threatening

loops of razor wire

coiling the wall-tops. Glass and mortar. Rebar

piercing the unfinished columns of houses.

Prayer flags of drying laundry. Lace and cotton.

Sometimes I walk long, far

from the city center. Doors

slanting like a blade. Little braziers

glowing in the shallow interiors. Glassed candles

barring the windows. A lisping kettle.

But at my little house I can burn a fire too. I can hang

my jacket from the canisters of gas

that lean against the kitchen wall. Green steel.

The color of caribbean sand. Sunday’s trumpeter

ascending the callé, waking the roosters.

Sometimes Maliyel, my friend, invites me over

for camel straights and espresso. Socorro, she tells me,

is not some kind of wind, but one

of the names of sadness. Things

we are strong for. Assistance. Succor.

Then her son, Galo, calls down

from his sleeping loft, Randáll, buenas dias!

Last night, at the Téatro, Endgame.

Capacity, eighty-five.

A cluster of pins

stuck in a wooden table

shining in a desk lamp’s half-dollar

halogen brightness. All mauve at the margins,

like a nineteenth century curtain.

Maliyel wondered if metaphor revealed a unity

hidden in the shape of things. What Paz conjectured,

though he’s dead now, of course.

Sun and stone. Speckles of quartz in a granite outcrop.

So this morning Galo and I play soccer.

I call it soccer because I live in Houston.

Maliyel comes out to watch, and is smiling.

He moves the ball between his feet, delicate,

precise, easing it with the outside of his foot

before he shoots. And we welcome it as it enters

into the air. There is nothing to protect. Nothing

to save. It is quite beautiful as it rises.