Jonathan Moody recently won the 2014 Cave Canem Northwestern University Press Poetry Prize. His second collection, Olympic Gold Butter, will be published in spring/summer 2015. He is the author of The Doomy Poems (Six Gallery Press, 2012), and his poetry has appeared in African American Review,Crab Orchard Review, Gathering Ground,Peter Doig: No Foreign Lands,Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Tidal Basin Review,Xavier Review,among numerous other publications. Moody received his MFA from the University of Pittsburgh, teaches at Pearland High School and lives in Fresno, Texas, with his wife and son, Avery Langston.

Jonathan Moody recently won the 2014 Cave Canem Northwestern University Press Poetry Prize. His second collection, Olympic Gold Butter, will be published in spring/summer 2015. He is the author of The Doomy Poems (Six Gallery Press, 2012), and his poetry has appeared in African American Review,Crab Orchard Review, Gathering Ground,Peter Doig: No Foreign Lands,Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Tidal Basin Review,Xavier Review,among numerous other publications. Moody received his MFA from the University of Pittsburgh, teaches at Pearland High School and lives in Fresno, Texas, with his wife and son, Avery Langston.

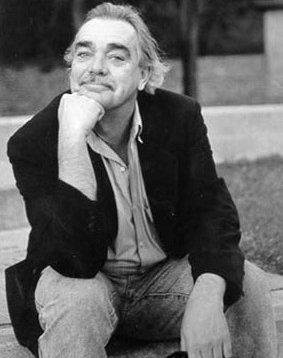

Larry Levis won the United States Award from the International Poetry Forum for his first book of poems, Wrecking Crew (1972), The American Academy of Poets named his second book, The Afterlife (1976) as Lamont Poetry Selection. His book The Dollmaker’s Ghost was a winner of the Open Competition of the National Poetry Series. Other poetry books include Winter Stars(1985) The Widening Spell of the Leaves(1991) Elegy (1997) andThe Selected Levis (2000) .In 1996, Larry Levis died of a heart attack at age 49.

Larry Levis won the United States Award from the International Poetry Forum for his first book of poems, Wrecking Crew (1972), The American Academy of Poets named his second book, The Afterlife (1976) as Lamont Poetry Selection. His book The Dollmaker’s Ghost was a winner of the Open Competition of the National Poetry Series. Other poetry books include Winter Stars(1985) The Widening Spell of the Leaves(1991) Elegy (1997) andThe Selected Levis (2000) .In 1996, Larry Levis died of a heart attack at age 49.

Eternal Reflection from the Gazer Within: An Essay on Larry Levis’s Winter Stars

If someone had asked me several years ago to describe Larry Levis’s poetry, I would have quickly responded with the phrase “lyrical narrative”. The term in question, though, is too vague and does not offer an accurate analysis that accounts for the slight edginess that asserts that he is engaged (i.e. politically conscious). For the most part, Levis is introspective and private. His extended metaphors unfold or rather tap into unknown dimensions. Instead of describing Levis’s work in a way that would tie him down to a particular style or school, I am more interested in focusing on what Levis avoids: Romanticism—a spectacular achievement coming from an individual who spent the bulk of his childhood pruning orchards on his father’s idyllic vineyard in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

To assign the word nostalgic to Levis’s work would be amiss. In “Poet at Seventeen”, the opening poem in Levis’s fourth volume, Winter Stars, his reflection would not take the form of a tight, tender embrace because his idyllic childhood setting was “so boring/ [he] memorized poems above the [tractor] engine’s monotone” and filled with “the kind/ Of solitude the world usually allows/ only to kings & criminals who are extinct,/ Who disdain this world, & who rot,…”(3). Levis’s use of hyperbole, comparing the solitude he experienced at seventeen to the loneliness of “kings & criminals”, is neither an immature ploy to win the reader over with ill-advised humor nor a billboard advertisement manipulating the audience into feeling sympathy (3). The exaggerated language evokes a slight uneasiness that demythologizes the trite notion of the wine country depicted as Paradise. Levis rarely, if ever, expresses raw emotion in his poems; however, it is interesting that his essays, which are as delightful as his verse, do not lack restraint.

In “Larry Levis: Autobiography”, a composition appearing in his essay collection, The Gazer Within, Levis’s stark tone conveys an intense pathos that never creeps its way into his poetry. When illustrating the devastating impact that urban sprawl had on his homeland, Levis writes:

My California, the vineyards and orchards on the east side of the San Joaquin Valley, have remained unviolated, for the most part by developers and suburbs. The land looks as if nothing has changed there. But that isn’t so. The land was settled, and then it was unsettled. My father and other small farmers, in order to keep up economically with a market that demanded earlier and earlier varieties of fruit, especially peaches and plums, tore out old orchards of Reynosa and late Elberta peaches and orchards of late plums and supplanted them with new varieties developed by University of California, Davis, that they could harvest in late May and early June…the new varieties of peaches had no flavor and no sweetness. Their flesh was tough instead of ripe and tender (6).

Levis’s use of the word “unviolated” evokes a tinge of sarcasm that’s not present in his poems, and his heartfelt account of how small farmers were compelled into becoming major businessmen (at the sake of growing a substandard product) portrays a helpless community unable to wriggle itself loose from the grasp of corporate greed. He continues expressing his frustration on what his beloved California has become when he references what significant damage poisonous chemicals like “DDT” and especially “parathion” will cause to the inhabitants of San Joaquin Valley (6). None of the anger in the aforementioned passage seeps into “Poet at Seventeen”. The emotion is thoroughly distilled down to a metaphor that conveys the vineyard as a place of oppression: “the vines must have seemed like cages to the Mexicans/ Who were paid seven cents a tray for the grapes/ They picked.” As mentioned earlier, the politically-charged language inherent in the previous lines is what makes me hesitant to label Levis as solely a lyrical poet. Here, we have the poet as witness acknowledging socioeconomic inequality. However, in the poem, he does not shout this injustice from the roof top; he makes a casual observation.

Like William Blake, Levis used the essay form to generate ideas for poetry. What made Levis feel the need to eradicate those details about the rapid changing in farming practices making smalltime farmers feel obsolete and the hazardous pesticides that “could affect the nerve endings”? Why does Levis see the essay as a better form to belt out his rally cry and see poetry as a funnel that should filter emotion? I often wonder if Levis is suggesting that restraint is what prevents a poem from becoming an essay or even a speech.

There are other poems in Winter Stars that I would like to explore as well: “Adolescence,” “The Cry,” “Family Romance,” and, of course, “Winter Stars” (my favorite Levis poem). The discussion is not limited to these poems (as I’m uncertain if all of the titles are available on-line).

An interesting thing to note is that some of the prose from The Gazer Within made its way into Levis’s poems. For example, as a child, Levis denounced his Catholic upbringing and inferred that it was impossible for human beings to exhibit altruism. These statements appear in “Family Romance”, and his recollection of his father stopping one of his workers from killing another man wound up manifesting itself into one of the greatest poems I’ve ever read: “Winter Stars”.

I’d also like to discuss Tony Hoagland’s assertion that, “Levis is not interested in metaphorical equivalence,” “in comparison as a device whose goal is logical coherence, or persuasion, or concentration; rather, his practice is to use image as a form of inquiry, as a kind of tentative, speculating finger poking into the unknown.”