Jenny Browne on Richard Hugo’s 31 Letters and 31 Dreams

The first poem I ever wrote was a letter. I was 19 and had left the Midwest to spend a year in Sierra Leone, West Africa. Like any good 19-year-old, I stepped off the plane with all sorts of eager notions about changing a world I had yet to see. Once there, I wrote loads of bad poems about sunsets and sent them across the ocean with a decidedly 18th century understanding of audience, knowing that it would take weeks, even months, for those pale blue tri-folded aerograms to arrive, and that they would surely be read aloud to rooms filled with my aunts, uncles, cousins and friends.

I probably should have taken the advice of some even earlier epistles, those of Horace, whose Letters to Piso serves to council on the art of poetry itself, suggesting that that we should read widely, strive for precision, find best criticism, and perhaps most importantly, wait at least nine years before showing our poems to anyone.

Eventually there was a coup, and I was evacuated from Africa in a C-130, but that’s a story for another day. Sometime that winter, back in Wisconsin, I walked out of a used bookstore clutching a two-buck copy of Richard Hugo’s 31 Letters and 13 Dreams. It had been a strange year, one that left me feeling like parts of my body remained on the other side of the world. At the same time, I felt confused as to whether any of what I remembered experiencing had actually happened.

Walking those dark snowy afternoons, I felt both isolated and over-exposed. Something in the weird backlight of Hugo’s cover—that x-ray of an open envelope with dead flowers falling out of it—grabbed me. I will admit that I often still buy books by the picture on the front. Wine too. This was all over was twenty years ago, but my most recent book of poems, Dear Stranger (University of Tampa 2013) also uses the epistolary mode, and in working on it I found myself returning to Hugo, wondering if the poems would still impact me as they once had.

Glimpsed from our current moment of near constant virtual correspondence, it’s difficult to imagine the literal isolation that troubles this book. Hugo’s letters narrate both geographic and psychic dislocation, as the speaker seeks to ground himself in relation to people and places, to regret and desire, and even to poles of sanity and surrender. Many of the letters end with the suggestion of, and devotion to, poetry as our most primal home.

Most of the poems are addressed to other known and recognizable poets, but Hugo also writes to a nun about his lady troubles, and to a former lover with surprisingly gentle and lyrical concern: “Oh, my tenderest/racoon, odd animal from nowhere scratching for a home,/please believe I want to plant whatever poem will grow/inside you like a decent life. ”

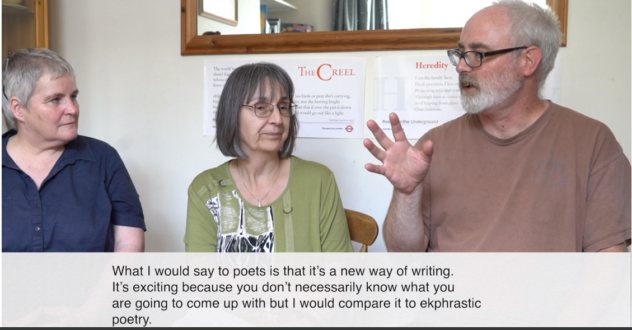

I think that good epistle poems—no, all poems, really—must demonstrate a clear reason for their existence, and one nice thing about letter poems is that they come with a built-in antecedent scenario, namely the performed suggestion that a real or imagined me sitting right here really needs to tell a real or imagined you out there something important.

Hugo’s epistolary impulses can feel alternately chatty and urgent, even desperate. One minute he’s grouchy or bored, and the next he sounds desperate to prove not only that what he sees exists, but that he can be seen, that he exists, at all.

Here’s a passage from “Letter to Peterson from the Pike Place Market,”

“Today, I am certain,

for all my terrible mistakes I did the right thing

to love places and scenes in my innocent way and to spend

my life writing poems, to receive like a woman

the world in its enduring decay and to tell

that world like a man that I am not afraid to weep

at the sadness, the ongoing day that is draining our life

and is life. Sorry. Got carried away. But you know, Bob, how

in the smoky recess of bars all over the world, a man

will suddenly dance because music, a juke box, a Greek

taverna band, moves him and how when he dances we

applaud and cry go. That’s nobility of blood, a recognition

by those who matter that in special moments

we are together facing the brute descent of the sun

and that cold brittle star we know already burned out.”

At times, such expressions of earnest, even confessional, sentiment sound as old-fashioned as, well, writing a real letter. But Hugo consistently complicates his own narrative certainty, and the dream poems that alternate between letters suggest a darker second person hovering just below the surface.

“In Your War Dream” begins and ends with the same insistent, circling line: “You must fly your 35 missions again.” And here come the last two lines of “In Your Fugitive Dream,” “You watch them search your luggage. Then/ you remember what you carry and start to explain.”

Letter poems also imply reciprocity, even if that response remains unheard, and I can’t help evoking Yeats’ famous “Out of the quarrel with others we make rhetoric; out of the quarrel with ourselves we make poetry” in suggesting that if epistolary poems are letters to others, maybe dream poems are letters to ourselves.

In Hugo’s book, both modes build dramatic tension for multiple audiences: the named recipient of the letter, the dreamer, the awake, the “you” that is both all of us and none of us, and last but not least, the “me” drinking coffee on my couch with the little thrill that comes with reading other people’s mail.

One of my favorites, addressed to Mayo from Missoula concludes,

“And if the saying of it

is, as Stafford says, a lonely thing, it is also

the gritty. Take the hard road home. That is the road you came on

long ago, without drum or banners, without some poet

trying and failing to praise you from the brush in some damn

fool poem like this one. I guess you get what I mean. I mean

take care now. Leave labor to slaves. Give my best to

Myra and show this letter only to trustworthy friends. Luck. Dick.”

I love letter poems, but in the end, I found that I returned to this book of poems for the poetry, period. I relished Hugo’s recognizable darkness, his delicious and occasionally vulgar particularity (tantric sex tips from Gary Snyder anyone?) as well as his thrilling tonal variation. He even throws in a good old-fashioned invective for good measure:

“May the bluebird of happiness

give you a venereal disease so rare the only known cure

is life in the tundra five hundred miles from a voter,

the only known doctor, a mean polar bear. May the eyes of starved

whores burn through your TV screens as you watch Lawrence Welk

I’m getting far from my purpose. I wanted to tell you I

I still owe your poems, then got hung up on people

who won’t leave people alone…”

The last reason I believe we should all read and reread Richard Hugo is for the way his lines remain consistently attentive to both the present and past, to how it feels to live in more than one place at once, tuned to the wild leaps of the subconscious as well the steady imagistic chink of the sensory world.

“Why do I think

of this today? Why, faced with this supermarket parking lot

filled with gleaming new cars, people shopping unaware

a creek runs under them, do I think back thirty some years

to that time all change began, never to stop, not even

to slow down one moment for us to study our loss, to recall

the Japanese farmers bent deep to the soil? Hell, Bill,

I don’t know. You know the mind, how it comes on the scene again

and makes tiny histories of things. And the imagination

how it wants everything back one more time, how it detests

all progress but its own, all war but the one it fights over

and over, the one no one dares win. ”

For me, 31 Letters and 13 Dreams constellates time, space, relationship, and the possibilities and limits of living in a temporal body. Hugo suggests a juxtaposition of inner and outer life that we can all recognize as human. And most importantly, these poems still really make me want to write back.